Our Collaboration

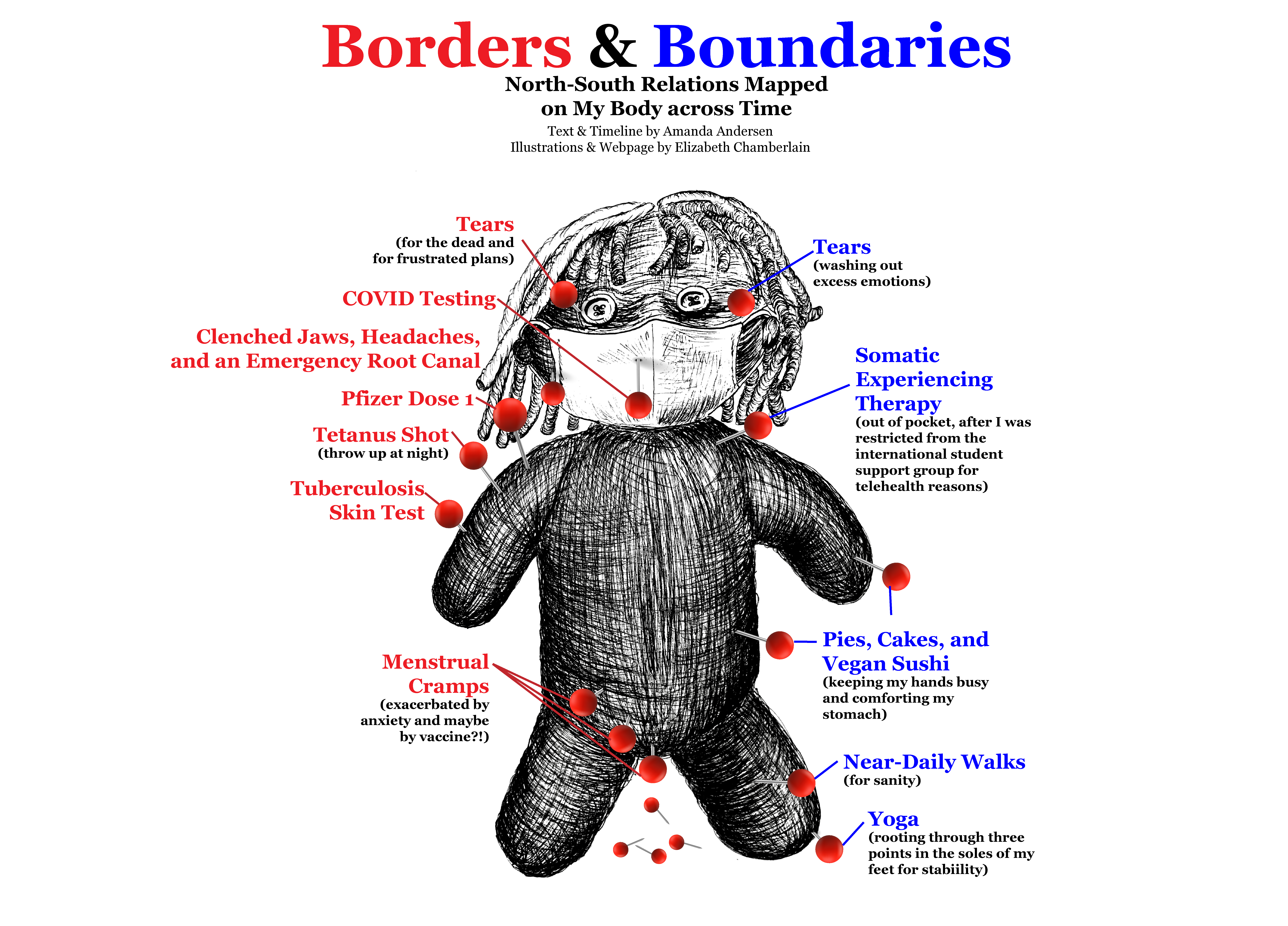

Amanda and Elizabeth joined forces via the JOMR call to collaboration, which asked participants to submit a brief description of their interest in the Carework issue, their experiences with pandemic care, and their technical capabilities. Amanda had a story to tell and a vision of a voodoo doll mapping her experiences; Elizabeth had some coding capacity and had gotten into drawing during the pandemic.

Elizabeth's Response

When I first heard Amanda's description of her experience, I was saddened and anxious on her behalf. What an awful way to begin a graduate program, with that series of extended uncertainties. International graduate studenthood must be a stressful and lonely enough experience even without the multiplier of the pandemic.

I have felt throughout the pandemic that I am lucky to have been spared the hardest pieces of it all: Unlike many of my friends, I have no children, and therefore didn’t have the logistical burden of childcare to sort out. Unlike the least lucky among us, my family has been vaccinated without deaths or many serious illnesses in my closest circle (though we did lose some family friends), and I was mostly able to hunker down (though I was mandated to return to in-person teaching during the Delta spike in August 2021 and saw many of my students infected). Unlike Amanda, I had none of the fears about visas and international graduate studenthood during a time of closed borders and restricted travel.

But as I got deeper into reading Amanda's story, I found more resonances in our experience: Tears for the dead and frustrated plans weigh on us all. My family all lives in California, and I was 2,000 miles away, teaching in Arkansas. I had been living across the country for eight years, but this was different: I went from January 2020–May 2021 without seeing any family at all. Though Zoom and phones enabled us to stay in touch, I learned just how much my sense of well-being depended on regular doses of hugs from family.

For months, I was so upset and worried sick that my period stopped entirely. I would start every morning by reading the case data for my county, my family’s county, and my university. Those numbers would run in my head throughout the day. I washed and Lysoled all my groceries until June. I ate only meals I cooked myself until September. I learned to keep hand cream in every room because I was washing my hands so often that they would crack and bleed from dryness.

I started therapy, near-daily walks, and a yoga practice to help me manage the emotional weight of pandemic living. I wrote poetry. I ran. I collected house plants. I joined a Zoom pandemic book group with old grad school friends. My cousins and I successfully cajoled my grandmother into giving us weekly Zoom watercolor lessons. A colleague started a Discord Dungeons and Dragons game, and I got to be a forest gnome named Flint Pufferfish on Monday evenings. I learned that online social connections could keep me tethered.

And ultimately, I decided to leave academia. Being so far from family had never before felt so much like exile, but I heard the existential clock ticking: I needed to be close enough to nurture those blood ties again. I’d hoped that someday I might be able to get an academic job in California, but when an opportunity arose to move back, I jumped at it.

This collaboration with Amanda has really brought home for me how many ways the pandemic has disrupted, shaken up, unsettled lives. I am grateful for the opportunity to reflect—still in the middle of the experience, but toward the tail end of that middle—and record for posterity some of the lived experiences of pandemic academic life that would likely otherwise go untold, lost in the enormous awfulness of the past few years for the planet.

I’ve learned something about what matters most to me.